Note to the Reader: I've moved platforms - my older posts are now hosted on Substack!

On August 6, 2007, the screens turned red.

At dozens of quantitative hedge funds, carefully constructed money machines were bleeding out. 2007 wasn’t a great year for the financial industry, but these funds weren’t getting hit by the sub-prime mortgage crisis. Not directly, anyways.

Most of them didn’t hold mortgage-backed securities, and some were even betting against MBSs. In theory, they were immune from the catastrophic losses in the fixed income market. Nor were they meant to be susceptible to the gyrations of the market as a whole. Dozens of PhDs had painstakingly and deliberately designed their portfolios to be beta-neutral: unaffected by whether the market went up or down.

Yet all of a sudden, these illustrious quant funds were losing hundreds of millions in a day, and no one had any idea what was happening.

The story of this so-called “Quant Quake” isn’t just the tale of how a couple of math whizzes screwed up for a few days. Rather, it distills the fundamental trade-off inherent in modern finance, between the need for legible strategies and the dangers of a crowded market!

No one is market-neutral in a foxhole

Renaissance Technologies. AQR Capital. Goldman Sachs Asset Manegement. Process Driven Trading Partners. Saba Capital. Highbridge Capital Management. D.E. Shaw. Citadel Securities.

These were some of the best quantitative hedge funds in the business in 2007, and investors loved them for their ability to deliver consistent returns, day in and day out. They were united by their overall approach: to buy undervalued stocks and sell overvalued stocks, in such a combination that the overall portfolio had approximately the same amount long as it had short1.

Of course, the way in which they executed this differed2, but regardless of the individual strategy, the theory was that this approach left them immune to the whims of the market as a whole. Even if some of their edge disappeared, it shouldn’t disappear simultaneously!

As WorldQuant’s Igor Tulchinsky put it:

“We knew that individual alphas regularly weaken or fail ... But our alphas were not supposed to fail collectively.”

Yet the signals didn’t just fade. They reversed.

Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion

How is it possible that all of these strategies would go so wrong all at once?

By August 9, Matthew Rothman had an inkling of what was going on. His memo “Turbulent Times in Quant Land” is the most popular piece of analysis Lehman Brothers has ever produced (or for that matter, will ever produce):

“There has been a systematic unwinding of factors bets as a few large investors need to reduce risk in highly liquid markets.”

In short, some multi-strategy funds took on losses in their fixed income portfolios due to the sub-prime crisis. Having borrowed to buy these sub-prime assets, they now faced margin calls from their brokers to cough up cash as these assets went to zero. To de-risk and raise cash, they unwound their positions in their most liquid portfolio: quantitative equity.

This meant that they sold the undervalued stocks which they had previously bought, and they bought up the overvalued stocks which they were previously betting against3. Because of how quickly they had to unwind and how large their portfolios were, this had a big effect on prices.

Overvalued stocks became even more overvalued. Undervalued stocks became even more undervalued. For market-neutral quantitative equity funds which rely on the market converging to the true theoretical price, this dislocation was painful.

The very success of market-neutral quantitative equity strategies in the early 2000s had led to an influx of capital into the space, with fund managers borrowing in order to juice up the returns. When prices went in the wrong direction, every fund in this crowded space had to dump their very similar portfolios at the same time.

The leverage worsened this synchronised sell-off, causing further fire-sales and short squeezes4. Without any buyers, everyone was selling into a vacuum, amplifying the magnitude of the price dislocation.

To quote AQR Capital CEO Clifford Asness:

“I looked up and saw the Valkyries coming and heard the grim reaper’s scythe knocking on my door.”

Not a pretty sight.

August slipped away into a moment in time

Just as abruptly as the “Quant Quake” began, it ended.

Out of the blue and for reasons which are still not entirely clear to this day, returns on quantitative equity strategies rebounded on August 10. Some attribute this to Goldman Sachs re-capitalising its asset management arm with a $3 billion bailout. Others credit AQR with their decision to start buying assets loudly and boldly.

Regardless of what exactly turned the tides, the crisis soon receded from collective memory, overshadowed by the far more public financial instability across the rest of 2007 and 2008. However, the “Quant Quake” was in many ways a far more interesting event than the subsequent chaos on Wall Street.

While the Global Financial Crisis was a classic bank run (if applied to some new institutions), the “Quant Quake” taught us just how much hedge funds have changed since Alfred Jones’s first “hedged fund” in 1949:

The Good. Hedge funds improve price discovery without being too big to fail. Market-neutral quant funds really were market neutral, and equity markets were not affected in the aggregate by the “Quant Quake”. Thus they owned their own risk: unlike many banks, they did not require public bailouts.

The Bad. Even in equities, which are one of the most widely traded markets out there, liquidity can dry up. There is enough overlap between quantitative equity strategies across funds that the stampede for the exit will cause prices to move.

The Ugly. Hedge funds are no longer negligible market actors. Like banks, they provide liquidity. Unlike banks, they can pull liquidity at a moment’s notice. Coupled with the growth of multi-strategy funds and the rising use of leverage, contagion can spread faster than ever, making them a source of systemic risk.

Playing the Elmsley count

Let’s hear from Asness again:

“I have said before that ‘there is a new risk factor in our world’, but it would have been more accurate if I had said ‘there is a new risk factor in our world and it is us’.”

This may have happened to quant funds in August 2008, but it isn’t exclusive to them. What this comes down to is a feature inherent in modern finance: legibility!

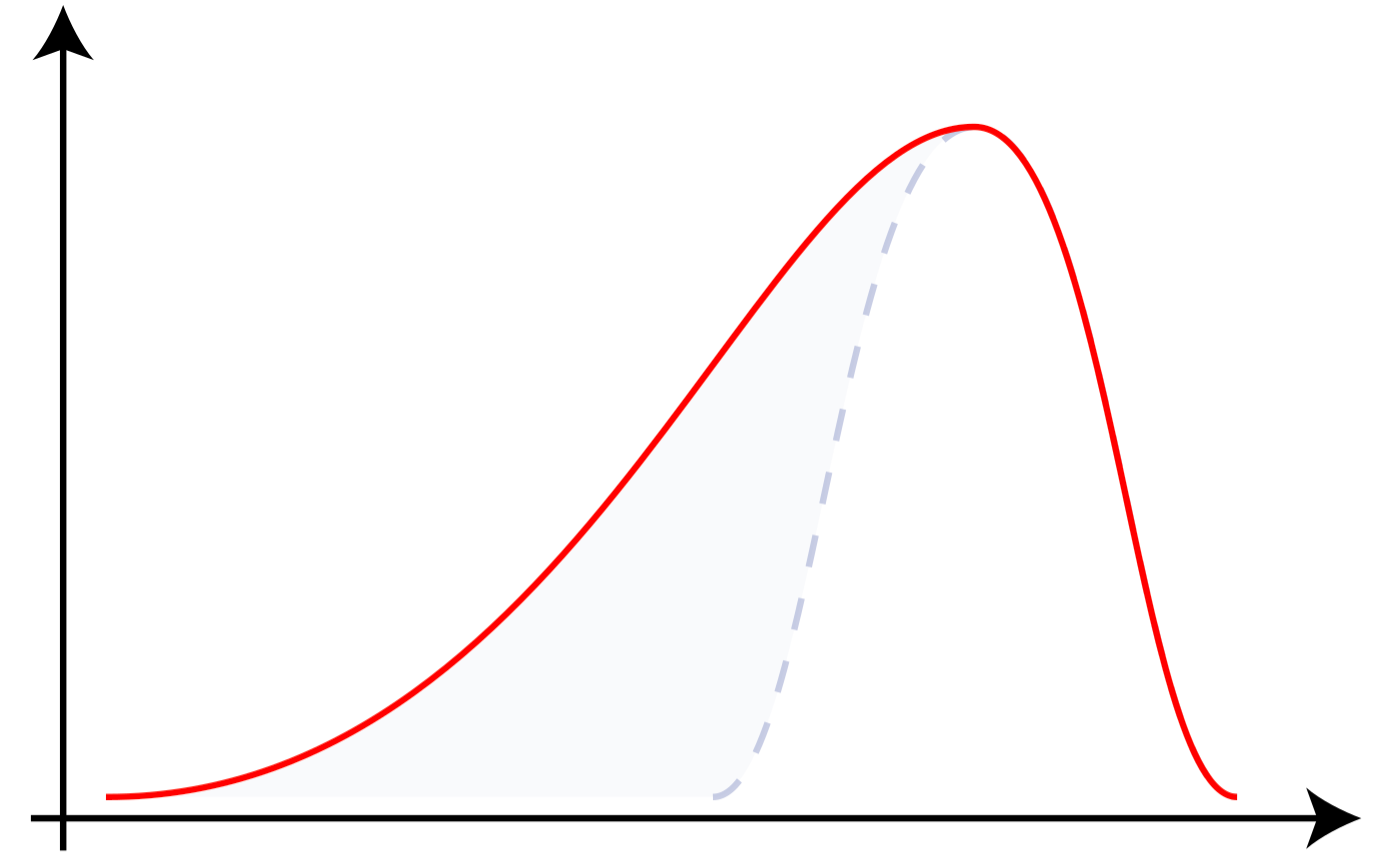

Investors like legible returns. They want systematic and quantifiable strategies with positive carry5. A broadly efficient market only gives you returns if you accept some risks. If you make money most of the time, you have to hold the tail risk of everything going wrong. This means returns which are distributed with negative skew, often described as “picking up nickels in front of a steam roller”.

If you previously had a symmetrically distributed asset with the same expected value as a new asset with positive carry and negative skew, it may look magical. You are miraculously earning money more often now than you did before. However, this isn’t magic. It is the opposite of magic. Indeed, the greatest trick financiers ever pulled was making us think they can destroy risk.

They can’t.

Risk simply represents some state of the world that is bad. Swapping cashflows does nothing to change the likelihood of those events. All that has occurred is risk transformation, by pushing the risk into the negative tail of the probability distribution. By its very definition, risk transformation cannot work everywhere and always.

However, these strategies do look good most of the time, and thus become popular as everyone wants to join the party. This crowding reduces the returns available, incentivising funds to borrow money and raise their returns. As everyone levers up with homogeneous strategies, the market becomes brittle.

When shit does hit the fan, it doesn’t just hurt one or two funds idiosyncratically. Rather, it acts as a systemic shock, and everyone tries to sell the exact same things at the same time. In this panic and at the moment where it is most needed, liquidity disappears and prices plummet. As then-Goldman Sachs CFO David Viniar said:

“We were seeing things that were 25-standard deviation moves, several days in a row.”

Thus it is almost natural that every successful strategy, like those used by quantitative equity funds, will become more crowded and become a risk factor over time6. In the trade-off between legible returns and the accumulation of tail risks, how do we strike an acceptable balance?

What the “Quant Quake” distills in the span of 4 days is one side of the equation: the market fragility associated with this pursuit of returns. In the next few weeks, I’ll be writing about the other side, cataloguing some of the ways in which financial engineering and risk transformation have been socially productive!

Further readings

Blake LeBaron’s 2001 paper on homogeneity in crowded markets: Financial “Market Efficiency in a Coevolutionary Environment”

Matthew Rothman’s hypothesis on August 9: “Turbulent Times in Quant Land”

Richard Bookstaber’s commentary on August 11: “What’s Going On with the Quant Hedge Funds?”

AQR CEO Cliff Asness’s Q&A in September 2007: “The August of Our Discontent”

MIT professors Amir Khandani and Andrew Lo’s analysis in September 2007: “What Happened To The Quants In August 2007?”

AQR CEO Cliff Asness’s defence of quant investing in November 2008: “We’re Not Dead Yet”

AQR CEO Cliff Asness’s 10 year retrospective in 2017: “The August of Our Discontent: Once More Unto the Breach”

Richard Bookstaber’s 2007 book foreshadowing the financial crisis: A Demon of Our Own Design

Sebastian Mallaby’s 2010 book on hedge funds: More Money Than God

Scott Patterson’s 2010 book on quant funds: The Quants

Ludwig Chincarini’s 2012 book on issues inherent to financial systems: The Crisis of Crowding

Gregory Zuckerman’s 2019 book on Renaissance Technologies: The Man Who Solved the Market

Taking a long position means betting in favour of an asset e.g. by buying it, while going short means betting against it e.g. by borrowing an asset from a broker, selling it to someone and buying it once its price falls to hand back to the broker.

Two of the most popular strategies were relative value statistical arbitrage (high frequency trading taking advantage of temporary divergences between cointegrated assets) and long/short equity (buying and selling stocks over longer investment horizons based on fundamental factors).

To make your net position neutral to some asset which you are long on, you just sell it. At most, you lose however much it initially cost. If you were short, you need to buy that asset to cover that short position, which means that there’s no upper bound to your losses.

A short squeeze is where the stock someone is shorting rises. To cover their position, those shorting may buy that stock, causing the price to rise even further.

An asset has a positive carry if it generates a profit from owning it, while negative carry means you have costs to cover from owning the asset.

As an aside for applied micro-economists, this feels a bit like how the proliferation of the rainfall IV has turned it from a way to tackle endogeneity to being a source of endogeneity.

"August slipped away into a moment in time"

Haha, that heading made me laugh. I just cannot read that line without it being Taylor’s voice in my head.