Last time, we established that GDP per capita matters!

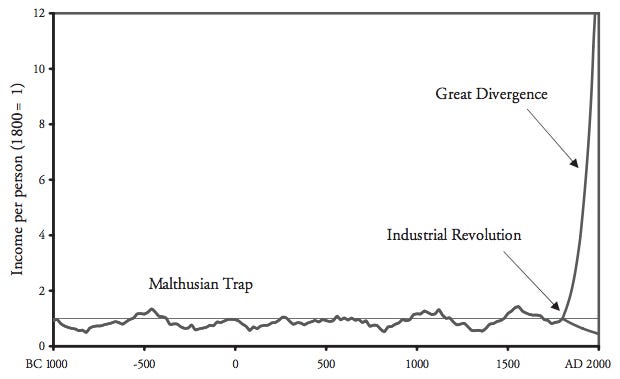

Yet for most of human history, GDP per capita has stayed at an absolute standstill. In A Farewell to Alms, Gregory Clark gives this three part history of economic growth:

From the time of the Middle Paleolithic Era (circa 100,000 BCE) when humans started migrating out of Africa all the way up till the late 1700s, the quality of life for humans was basically identical. If anything, the advent of agriculture and settlement meant that life after the Neolithic Revolution (circa 10,000 BCE) was worse than in hunter-gatherer times.

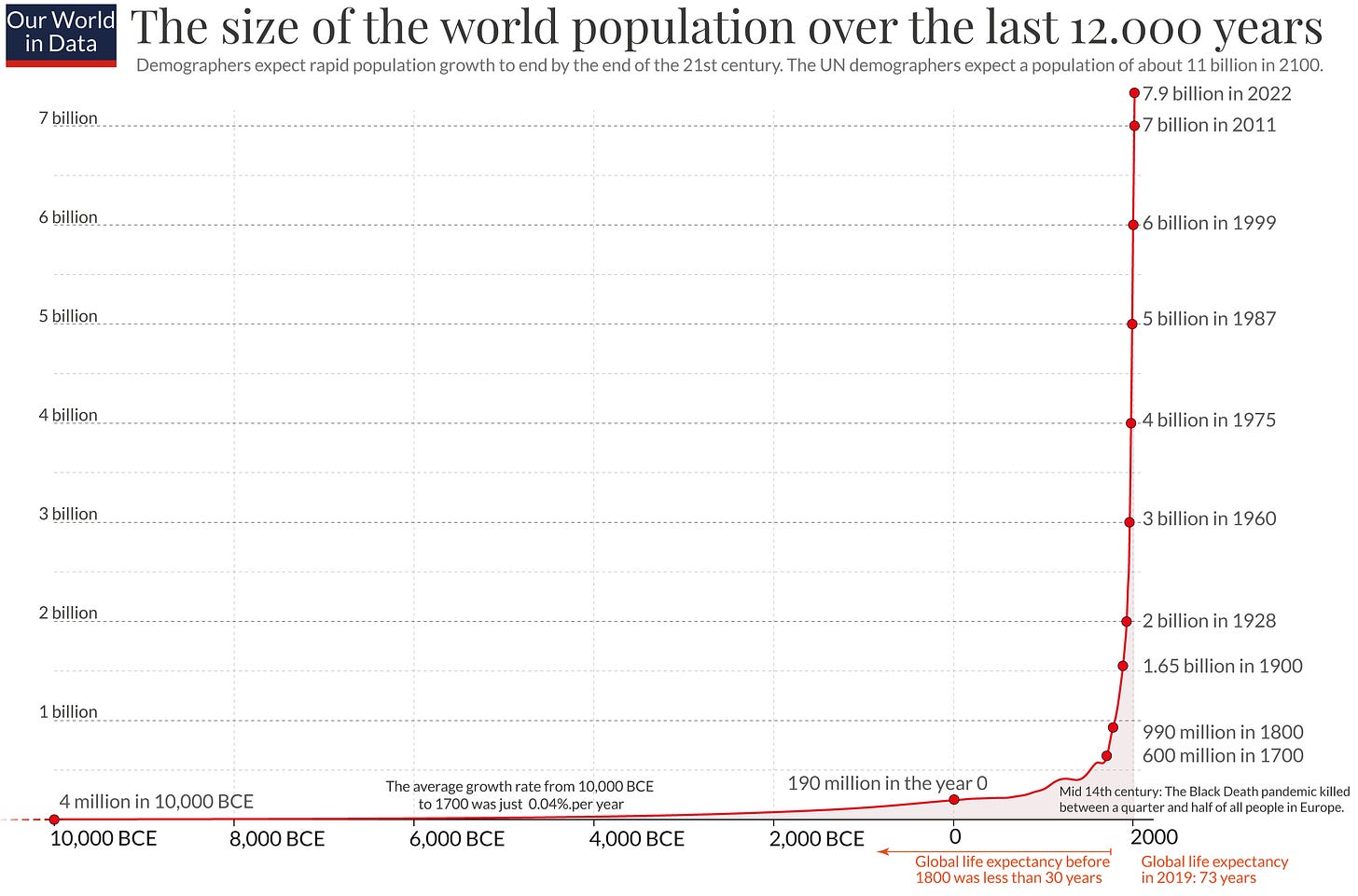

Humanity was stuck in a Malthusian trap, where any gains in material living standards were lost to population growth. Then, all of this changed with the Industrial Revolution. The total population in the world, as well as their living standards, both rose exponentially:

While it started in the UK and soon spread to many other countries in the world, this prosperity didn’t reach everyone. The Industrial Revolution caused a Great Divergence: while the richest modern economies are ten to twenty times wealthier than they were in the 1800s, the world’s poorest live in countries where living standards languish well below pre-industrial norms. Thus the gap in incomes between the richest and poorest countries is on the order of 100 to 1.

If we want to understand how we got to the world we live in today, we need to understand the Industrial Revolution!

The spectre of Malthus

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, a popular view was that of Thomas Malthus’s: continuous improvements in living standards were not possible! Because all the factors of production are fixed in supply except labour, the best we could get was more output via a larger population.

Of course, that means there would be no increase in output per capita! To make matters worse, there are probably diminishing returns to labour, so we would eventually run out of resources to keep growing. Even if there were, any improvements in living standards would lead to greater fertility, causing population growth until living standards re-equilibrated.

In many ways, Malthus got unlucky: he was basically correct, right up till the point he wrote his “An Essay on the Principle of Population” in 1798. For example, Malthusian theory would suggest that the Black Death would temporarily increase GDP per capita. It did exactly that: the drop in England's population from 6 million to 3.5 million people caused real wages to triple in the next 150 years, though by the 1500s, real wages were back at pre-plague levels.

Farming and fecundity

In the run up to the Industrial Revolution, there were two crucial secular changes occurring which would render Malthus’s predictions incorrect. The first is John Hajnal’s so-called Western European Marriage Pattern, whereby increased labour demand after the Black Death meant that women had more options instead of getting married. Coupled with religious norms against sex outside marriage, this led to lower marriage rates and fertility than seen elsewhere in Europe.

The second is the Agricultural Revolution. Starting from the 1600s, yeomen farmers had begun adopting all sorts of improved agricultural techniques, such as the use of nitrogen-fixing crops, convertible husbandry, land improvements and agricultural specialisation. Thus agricultural productivity saw a growth rate of around 0.4% a year by the late 1700s. In concert with this was the rise of coal, which meant that a smaller fraction of agricultural output was used as a source of energy and more could be devoted for food production.

The combination of limited fertility and rising food output meant that the Malthusian equilibrium in the UK was one with a smaller population and a higher living standard. This drove the Industrial Revolution in three ways.

Firstly, it led to higher wages, which incentivised the invention and adoption of labour-saving technologies. Secondly, it caused people to have more disposible income, with agriculturalists consuming over 33% more on manufactured goods than before. This created demand for the proto-industry of artisanal manufacturing. Thirdly, it meant that fewer workers were needed in agriculture, allowing them to shift into the proto-industry.

While over 70% of the population was working in agriculture at the start of the 1600s, by the 1800s this number was down to 25%. At the same time, industries like textiles were exploding, with a 150% increase in output during the 1700s. It would be easy to assume that all of this led to an immediate improvement in living standards, but in fact, they did not budge at all!

Population, not wages

While initial estimates suggested real wages rose by 80% between 1820 and 1850 alone, subsequent research has cast doubt on this narrative. Once incomes are considered at a household rather than individual level, once they have been adjusted with more realistic price indices and once the reduction in leisure time is taken into consideration, it looks more like stagnation than anything else. Indeed, anthropometric measures like life expectancy or average heights corroborate this dismal outcome.

That’s not to say that the First Industrial Revolution wasn’t revolutionary. Rather, its defining characteristic was the maintenance of existing living standards but with a far larger population. In the long eighteenth century, England saw its population triple to 18.5 million! This broke through the prevailing Malthusian equilibrium of 5.5 million which had persisted till the early 1700s. Although the immediate aftermath of the Industrial Revolution may not have increased GDP per capita, the industrial economy it created via a larger population would do exactly that!