GDP per capita is a fundamental concept in social welfare: it's pretty intuitive that if you live in a country which can produce more stuff, you're probably better off! Yet, it's a far larger part of the economist's toolkit than the social theorist's. In fact, critics of economics often deride GDP as an irrelevant anachronism of national accounting.

Here's Bobby Kennedy back in 1968:

“The gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. [...] It measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.”

All of this may well be true, but the question remains of how we can measure social welfare! Two stories appear most compelling to me: one is the subjective wellbeing approach, while the other is the capabilities approach. The former says that people are better off when they feel happier, while the latter says that people are better off when they can do more things.

How you doin'?

The subjective wellbeing approach has a certain purity to it: bettering people’s lives should result in people feeling like they are better off!

If we go with this approach, an easy way of measuring this is by asking people how they feel. People tend to know themselves pretty well, so it makes a lot of sense to hear it from the horse's mouth. In this way, self-reported happiness is a useful outside view which makes the fewest assumptions possible about what matters morally.

However, one significant obstacle to this is the Easterlin paradox: while happiness tracks income within and without countries at any particular point in time, it does not over the long term. One reason for this is a hedonic treadmill effect, where people are initially happier when they get richer, but adapt their expectations over time to expect their new level of wealth.

In particular, people care a lot about their relative income, both relative to others in their society and relative to their past self. This is why we see short-term effects in lottery wins and in recessions, but do not over longer time horizons (>20 years).

This means that there are policies which will raise GDP per capita, and thus make people happier now, but in 20 years, people will be no happier than they were before the policy implemented. The fact that it gives time-inconsistent implications for policy interventions means self-reported subjective wellbeing is crippled as a decision criterion for social welfare.

Three letter acronyms

Let’s now turn to the capabilities approach.

This is what GDP per capita is motivated by: if your country produces more stuff, you can do more stuff. Of course, it misses a few crucial contributors to human welfare, such as leisure, inequality, health and so on.

That’s why people look at alternatives like the OECD’s Better Life Index or the UN’s Human Development Index. The problem is that they vary in which factors they consider crucial towards human welfare, as well as the relative moral weights assigned to each factor.

For example, the BLI includes 11 factors which contribute to wellbeing: housing, income, jobs, community, education, environment, governance, health, life satisfaction, safety and work life balance. On the other hand, the HDI is nothing more than the weighted average of GDP, life expectancy and education levels.

It’s not clear that there’s an easy “ground truth” about how to consider all of these instrumental inputs, and which three letter acronym we should trust. Does that mean we have to give up on the capabilities approach too?

Revealed preference reveals

No.

One way to avoid the arbitrary choices associated with these indices is to try and find the most fungible inputs which contribute to people's capabilities: having resources and being able to use those resources. (Everything else can be “bought” with one of the two.)

A theoretically consistent approach to do so is the Jones-Klenow measure. Loosely, it views resources as inequality-adjusted consumption per capita and measures the ability to use those resources as lifetime leisure.

More formally, it models expected lifetime utility as follows:

Begin with an annual utility function which depends on consumption and leisure.

For each year, multiply by this by the likelihood of still being alive by that age and by a discount factor which represents people’s impatience.

Sum these up across 100 years.

Take the expected value.

I really like this approach!

To begin with, Jones and Klenow look at consumption per capita, rather than GDP. This is fantastic! GDP measures output, but that makes no distinction between stuff consumed or resources invested. The problem is that investment isn’t an inherent good. It’s only instrumentally useful because the resources it provides can be consumed later, and the welfare-relevant quantity which should be included is consumption.

Next, they adjust for inequality in an incredibly neat way. Economists tend to use utility functions which are concave i.e. those with diminishing marginal utility as income increases. This is the mathematical way of representing why inequality is bad!

One of the cool features of concave functions is Jensen’s inequality: the expected value of a concave function applied to some variable is less than the concave function applied to the expected value of that variable. Thus by taking the expected value of the lifetime utility function, they manage to incorporate inequality in a theoretically consistent way.

After that, they manage to take into consideration leisure time. Suppose one country has 10% higher consumption per capita than another. If that’s driven by everyone working 10% harder or longer, it’s hard to say that those living in the former are clearly better off.

Naive measures of welfare ignore this, or at best, include in a clunky and arbitrary weighted way. What Jones and Klenow do is that they look to the enormous literature in economics on estimating utility, which gives us numerical parameters about how people trade-off consumption and leisure.

Finally, when they are integrating the annual utility function over people’s lifetime, they multiply by the probability of being alive at that age. This provides a natural place for life expectancy to be inputted into the calculation: the benefit of being alive is being able to do stuff!

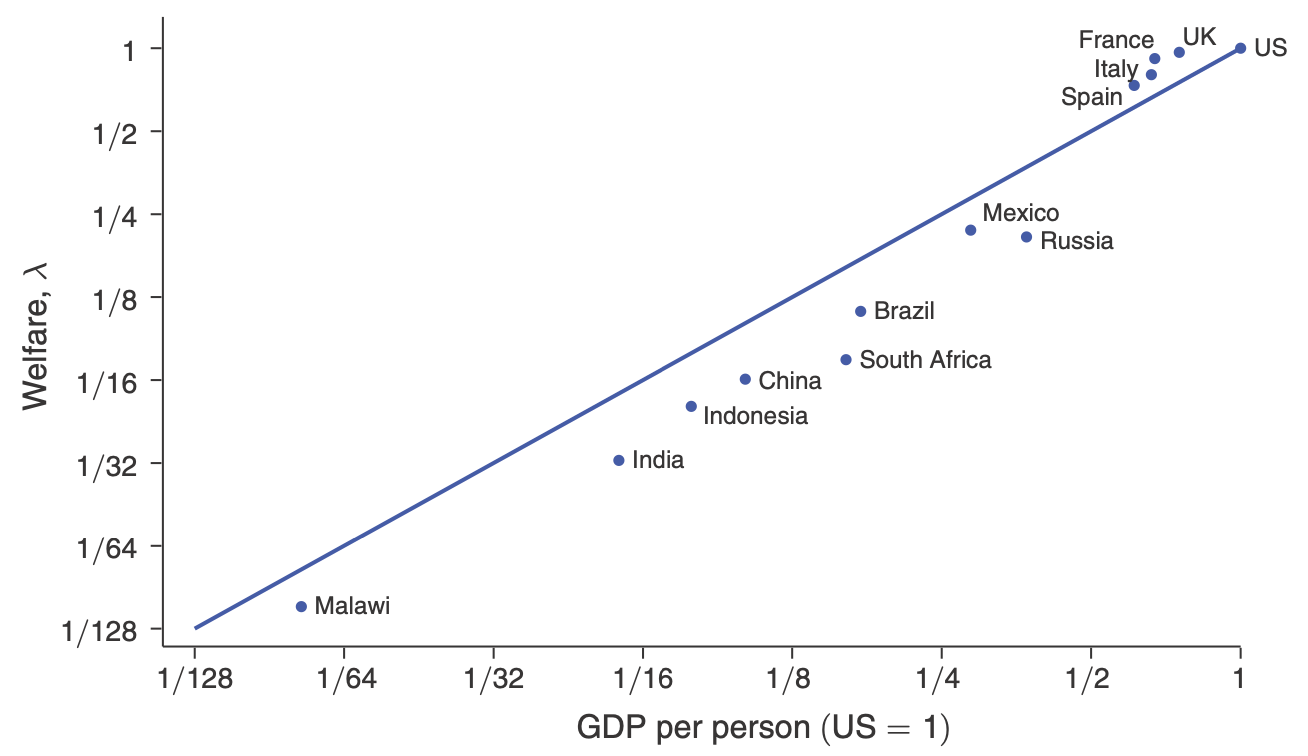

Yet despite all of this work, here’s what this Jones-Klenow welfare measure looks like when plotted against GDP per capita:

The correlation coefficient? 0.98.

Punchline: after all of this extra complication, the thing which matters for people’s capabilities is simply the production possibilities of the country they live in. GDP may well be the worst measure of welfare, except for all of those other forms that have been tried.